____ ____ ____ __ __ __ ___ ____ _ _

( _ \( _ \( ___) /__\ ( \/ )/ __) (_ _)( \( )

)(_) )) / )__) /(__)\ ) ( \__ \ _)(_ ) (

(____/(_)\_)(____)(__)(__)(_/\/\_)(___/ (____)(_)\_)

___ ____ ____ ____ ____ _____

/ __)(_ _)( ___)( _ \( ___)( _ )

\__ \ )( )__) ) / )__) )(_)(

(___/ (__) (____)(_)\_)(____)(_____)

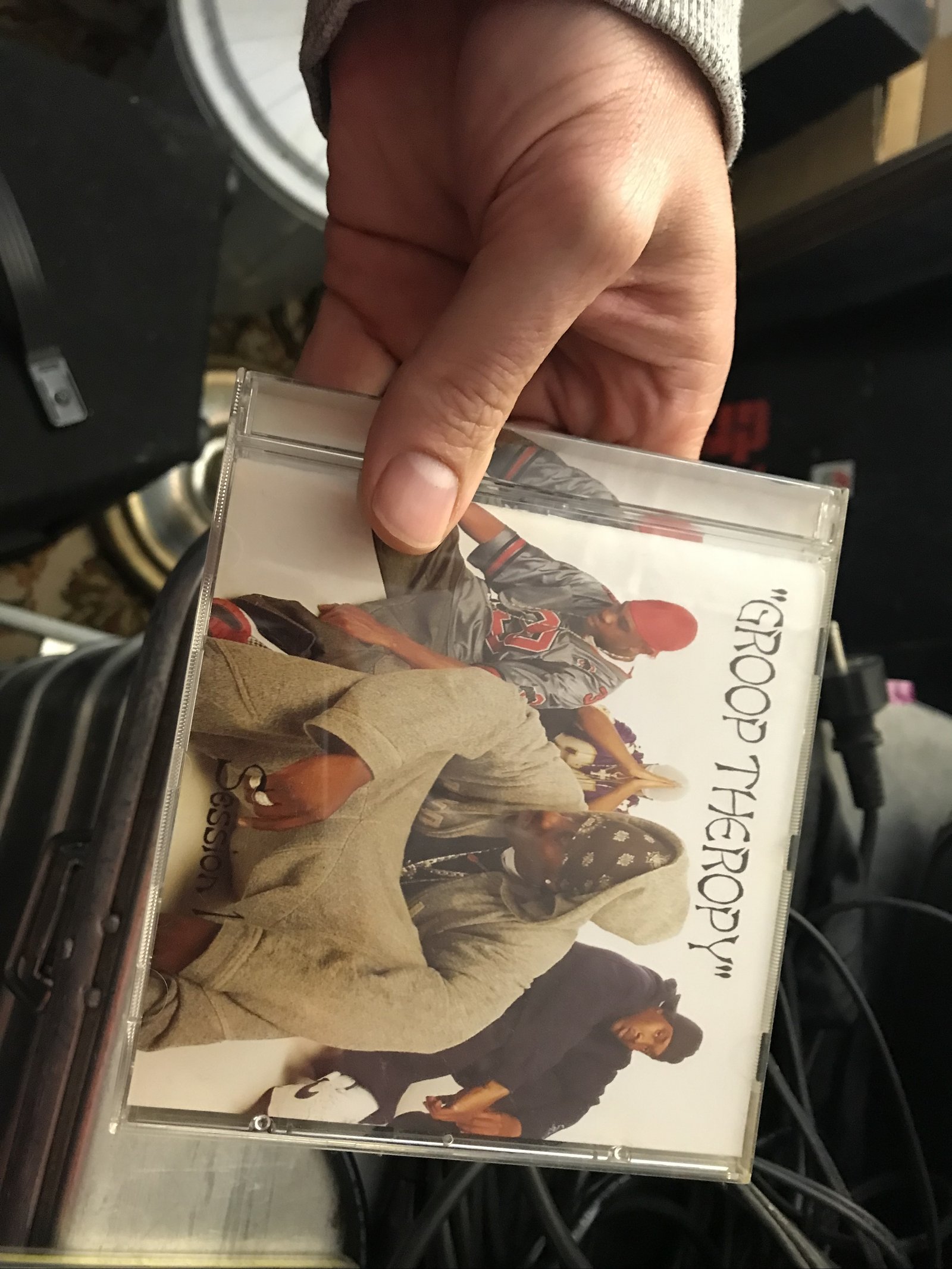

It took a long time for Heiko Hübschmann to find a free date when to meet me for a talk. The owner of the Friedberg recording studio Stereoblue is constantly on the road, always under pressure. Since it's difficult for a recording studio to support a family of four, Hübschmann has expanded his field of activity, overseeing and organizing the German concerts of big acts like Metallica, Beyoncé and many, many others. When we meet in the basement of Gutenbergstr.7 in June 2023, it's high season. "Just one more phone call and we're ready to go, but unfortunately I don't have much time. It's just crazy right now," Hübschmann, who was born in Bad Nauheim in 1979, greets me. I had already asked him for the interview 14 months earlier, when I came across an old article from Stars and Stripes about an American GI who had recorded a record with Hübschmann at Stereoblue on which he had musically and lyrically processed his experiences of the Iraq war. During our first brief conversation, Hübschmann immediately hinted that Josh Revak, the name of the music-making GI, was far from being the only person who walked the few yards from the barracks over to Gutenbergstraße to buy studio time with the versatile sound engineer Hübschmann."I estimate there have been about 50 GI's that have recorded with me over the years. At times, that has accounted for 20% of my orders," the 44-year-old reported. But how exactly did it come about? Hübschmann himself has to rummage a little in his memory. Then a name comes up. "Sam, yes, that was his name, he led a tank brigade. He was the first to approach me." However, Sam himself was not a musician at all. For his time after the military, however, the officer had a career as a music manager in mind. He wanted to start his successful career with a black boygroup that he had cast together in the barracks in Friedberg and Giessen. In tow at the time, Sam had another former GI who was to provide the beats and produce the band at a professional level together with Heiko. "That was Jeffrey Hannah." The boy band, named Groop Theropy, unfortunately remained unsuccessful, despite professional sound, songs that had the makings of a hit and elaborate PR.

What had proven to be extremely productive, however, was the collaboration between Jeff and Heiko. Even without Sam and Groop Theropy, the two continued, dreaming together the dream of the big breakthrough. Jeff supplied the beats, and recruited young black soldiers in the Ray Barracks, with whom they wanted to make the breakthrough together. Heiko, who until then had no great interest in hip hop, worked his way into the material and delivered the appropriate sound at major label level. But not only that - after all, these were special times. The American soldiers, who a few years earlier had been accused of being mainly busy killing time and bringing their pay to the people, had been on tour again and again since 2001, as they say in army jargon - in Kosovo, Afghanistan and finally in Iraq. So were the young musicians Jeff and Heiko worked with regularly. Time and again, work on their careers in civilian life was interrupted by war missions. Back came traumatized, wounded soldiers who wanted to process their experiences in songs. For many of them, Stereoblue was also a place to musically and lyrically process what they had experienced, and Heiko Hübschmann and his colleague Jeff provided the necessary infrastructure and creative support.The fact that you could record at Heiko, and in excellent quality, got around among the white GI's and so there were soon two factions in Stereoblue in the hand - black GI's with interest and skills in the field of hip hop and rap, and the white soldiers, who put their focus more on rock music and country. But not only the musical styles and skin colors differed, but also the expectations associated with their own output. If the white guys (in fact, not one female GI showed up at Stereoblue in all those years) produced more for themselves, their families, friends, etc., the goal of most rap artists was success on the charts, the big breakthrough. They wanted to make it in Germany, in the European market. "They certainly had what it takes," says Hübschmann. Unfortunately, nothing came of any of the up-and-coming young talents of that time. Not one artist could be placed with a major label by the German-American producer team. "That was, after all, the only option at the time." Streaming services, like Spotify, which nowadays allow everyone to release his/her music, didn't exist yet. Indie structures in rap and hip hop were completely different at the time and almost harder to reach than the major record labels. "That really got Jeff down." Both were sure that they were producing at a very high level, in tune with the times, and that it would work. Again and again, promising dynamics began to emerge. One day, for example, the Australian documentary filmmaker George Gittoes appeared in Hübschmann's studio. Gittoes had bypassed the U.S. government's media blackout in Baghdad and had made the film Soundtrack to War there, which was about the importance of music for soldiers deployed in Iraq. The unit Gittoes was traveling with, which he also portrayed, was from Friedberg.

Josh Revak in George Gittoes excellent movie "Soundtrack to War", 2005

The soldiers had told of their musical dreams and their collaboration with Heiko. Gittoes wanted to get a picture and spent a day documenting the recordings in Heiko Hübschmann's studio. What happened to the material is unclear. Nevertheless, Gittoes presence caused a stir, because Michael Moore, the famous documentary filmmaker had used some sequences from Soundtrack to War for his film Fahrenheit 9/11, and thus also brought the musical potential and talent of some Ray Barracks soldiers to the world. The American music industry took notice, famous musicians, like Pablo Petey wanted to feature the rapping soldiers, to bring them to public attention and support them. In fact, the whole thing took off, the excitement and the belief in the imminent success grew.

Famous guest at Stereoblue!

But in the end, the nascent collaborations came to nothing as well. Hundreds of unreleased songs, of whose breathtaking quality I could convince myself in the studio, still lie on the hard drive of Stereoblue, and will probably never be released, even if thanks to streaming services etc. nothing would stand in the way of a release. But a lot of time has passed. Jeff and Heiko are no longer in contact. Where the musicians from back then are today, how one could reach them, is unclear. Heiko knows it would be a mistake to simply put something like that on the net. What if one of the GI's who stood in the recording booth in Friedberg in the noughties would be a successful musician with a major label contract today? What would such a label do if suddenly tracks of a signed artist would appear? Heiko doesn't know, but prefers to remain cautious. He also prefers not to give me the songs - understandable. But then he remembers that there was this one song that was not meant for a larger audience. Josh Revak, who had returned from Iraq with a leg injury, had the idea to send a musical Christmas greeting to his comrades at the front. A CD with productions from Stereoblue Studio. Through their love of music, the country and rap factions had grown closer, appreciating each other's talent and creativity, and so they formed a kind of Stereo-Blue supergroup for the project. Jeff and Heiko also recorded video greetings from the families left at home to the GI's in Baghdad in their studio. Hübschmann remembers great emotions, many tears. Parts of these greeting messages found their way into the song Arm Support Radio as samples, as well as the voice of the commander, who sends a greeting message to all his servicemen and women via the satellite telephone. The song gets under the skin, again and again children's voices longing for their father push between the hold-out lyric and the stomping beat. A piece of contemporary history that Hübschmann fortunately makes available to me.

We can only hope that the many, many songs that the Hübschmann/Hannah production team recorded at Stereoblue Studios will one day find their way into the public domain. They are authentic testimonies of humanity in an unjust war, of the will to succeed, and not least of a musical tradition in the Ray Barracks that does not begin and end with Elvis, but is closely connected with the involvement in world political events and the social reality from which the GI's come. Many of them did not want to return to this American reality in which they saw no chance for themselves, and tried to gain a foothold in Germany, even if it did not work out with the musical career. "Almost no one made it," says Heiko Hübschmann, "not even Jeff." Despite his wife and children, the former soldier was unable to gain a foothold in everyday life in Germany. After a long night in which Heiko and Jeff listened through all the productions of the past years again, Hübschmann took his friend and colleague to the Frankfurt airport and bought him a one-way ticket back to the USA. "It just wasn't meant to be," says Hübschmann, whom our conversation made thoughtful and led deep into his own past. But there's the phone ringing again- in a few days, Hübschmann will be back on tour. "It's just crazy right now," he says once again before I leave Stereoblue and head off to my next interview.